In the era of climate change and harmful practices in agriculture, initiatives that promote traditional techniques with focus on striking balance with nature and keeping local conditions in mind have to be appreciated. Such initiatives have started taking roots over the past few years, but some of them that have been pioneers and successfully changed the lives of farmers and also environment need to be talked about.

One such initiative has been playing out successfully in the villages of Unchehara block of Satna district for quite some years now. The initiative is based on conservation and use of indigenous multiple varieties of seeds for farming coupled with organic farming measures and has truly changed the lives of local farmers – many of them tribals, while ensuring that the harm to environment is minimized or even negated.

Padma Shri awardee social worker Babulal Dahiyaand his organization Sarjana Samajik, Sahityik and Sanskritik Manch are the flag-bearers of the initiative that could be understood only when described in details.

Let’s then talk about the Baghelkhand plateau in Satna, its unique people, their ways of life and the game-changing return of traditional farming in 30 villages in Parasmania Pahad area.

Introduction

Satna district is situated on the northeastern border of Madhya Pradesh and part of the Rewa administrative division. Geo-physically it is part of the Baghelkhand plateau. Satna district could be divided into two parts – the hilly range and the plains. The hilly range is mostly inhabited by the tribal people. Here we see farming of nutritional coarse grains like kodo, kutki, maize, arhar and paddy. The soil here is light yellow. In the plains, paddy and soybean are grown. The soil here is black loam.

Satna district is surrounded by Kaimor hills in west, Panna hills in north and Parasmania hills in the south. At one time, these areas were covered by dense green forests, but now the hills are as bald as a shaven head. The local rivers are Satna and Tamas, which were perennial earlier but are slowly drying up. The local language is Bagheli, but people also speak Hindi. The district has several cement factories.

The Sharda Devi Temple in Maihar of Satna is very famous and sees a crowd of devotees all year round. There is a belief that during the exile of Lord Ram, he spent long span of time in Chitrakoot of Satna with wife Sita and brother Laxman.

Parasmania Pahad and Tribal People

The hilly area houses 84 villages with dominance of Gond, Kol and Bhumia tribal as settlers. There are several sub-tribes of Gonds in the area. From 15th to 18th century, Gonds ruled over some parts of Madhya Pradesh and the tribe still forms a big chunk of population in the region. Most of the Kols are landless and very poor. They work as agriculture labourers and often migrate for work. They are in a small number and their villages are on the edge of the Pahad. They also sell firewood as source of sustenance. Bhumias have a good knowledge of herbs and medicinal plants found in the forests.

It is in 30 of these villages of Parasmania Pahad that Babulal Dahiya– the conservator of indigenous seeds and his Sarjana Manch have initiated traditional farming with the use of indigenous seeds and organic farming measures.

In this region, agriculture is rain-fed and the main crops are coarse grains like kodo, kutki, sanwa, kakun, maize, jowar and bajra. Indigenous paddy is also sown and it brings the farmers cash that could be used for domestic expenses.

Mixed Farming on Pahad

Melma or Mishrit Kheti (Mixed farming) is practiced in the Parasmania Pahad region. It is also known as Milwa kheti in Bundelkhand. Tribal people have been practicing this mode of agriculture since ages. They have been saving indigenous seeds through generations, passing it over to the next generation. They have always practiced farming ways where the crop pattern was in consonance with climate and weather and based on indigenous, diverse quality of seeds.

These tribal people grow not one or two but up to six or seven crops together, in what is known as multi-layered farming. For example, along with jowar, they sow crops ranging from ambadi, arandi, arhar to til, barbate, okra (bhindi), udad, mung and others.

Using the multi-layered cropping pattern, they sow Jowar at the highest level (7-8 feet), followed by arhar and ambadi at 5 feet, til at 4 feet, okra at 4-5 feet and mung and udad at 2 feet height. Ambadi is sown on the boundary of the farm and works for protection of crops too. Barbati creepers grow over the Jowar plants. Some farmers also sow maize, kakun and cucumber in between.

These multi-crops do not harm, rather help each other. The time of harvest is also different. First Jowar is harvested and when the crop is cut, arandi and arhar get more space to grow. Barbati grows over the arandi plants and udad and mung grow as shrubs at the lowest levels.

All crops ripen and are harvested at different times and this helps in maintaining the health of the soil. Bean plants provide the nitrogen and thus additional fertilizers are not required. These crops together make provisions for food for people and fodder for the animals. In mixed farming, animals, especially cattle play a big role. They get fodder from the farms and their dung is used to make fertilizers, in turn making the soil fertile.

Since the early ages, jowar was used to make chapattis, til gave the oil, ambadi provided raw material to make ropes, arandi gave fruits and also oil for lamps, mung and udad provided the pulses protein. Okra and barbati beans were used as vegetables. It is this wholesome farming pattern, which is being promoted again in the villages of Parasmania Pahad – where a single farm gives you the basic grains, legumes, pulses, oil seeds, vegetables and even fodder. It is indeed an arrangement for nutritious meal and self-sufficient life.

Plains, Farmers and Farming

The main crops in the plains are wheat, paddy and soybean. The irrigation facility is limited here too. The facilities available are canals of the Kulgadhi reservoir and tube wells. Canals of Bargi dam have been construction, but they are not functional yet. Apart from Kurmi, Dahiyaand Brahmin communities, there is a large population of Kushwahas too in the area. The Kushwaha community members undertake vegetable farming. Earlier, the groundwater level was so high that the farmers normally dug into earth with bare hands to get water for irrigation. If the temporary wells would fill up with mud during the monsoons, they would be dug up again. But now the groundwater level is dipping constantly.

Drought, Migration and Traditional Farming

For the past few years, the region has become drought hit. Most affected years were 2014 and 2015. I was in the region at that time. In 2015, hand pumps had dried up, there was no water in the ponds and standing crops had dried up on the farms. There was scarcity even of drinking water and villagers were migrating to urban areas in search of livelihood. Only elderly people were left in the villages.

Though migration is not new for the region, but the repeated drought years aggravated the conditions. Deforestation, negligence of ponds and constant mining has turned these areas bare, dry and drought-hit.

Indigenous seeds are important in these regards as there are diverse varieties and they can grow with less water and in dry conditions. Some indigenous seeds-based crops can ripen even with dew water. The initiative of Sarjana Sanstha is therefore making a lot of difference in the conditions of drought, economic distress and inclement weather. Indigenous seeds based farming has ensured meals and food security for the locals.

Babulal Dahiya says that one of the reasons for rampant migration was that the farmers could not get good rates for their crops. Sarjana has therefore tried to find market with good rates for the crops of local farmers. The organization makes arrangements for sale of crops in several big cities of the country.

Sarjana Samajik, Sanskritik Evam Sahityik Manch

Babulal Dahiyais basically a Bagheli poet and litterateur. By profession, he was a postmaster and since retired. He stays in the Pithorabad village in Unchehara block of Satna district. Government of India honoured him with the Padma SRI award in 2019 for his work on indigenous seeds. He has registered the Sarjana Macnh in the year 2003. Dahiya has a deep interest in folk literature and culture. He shares that earlier he would compose and compile folk songs, folk sayings, idioms and folk literature. Then he felt that since much of the folk literature, idioms and sayings were on food grains, it was important to save the indigenous grains too. Also it was important to conserve and promote traditional farming and indigenous seeds along with the folk literature. It is with this objective that Dahiyaand his Sarjana Manch are constantly endeavouring to conserve and promote traditional farming, seeds and crops.

Sarjana has undertaken a lot of steps for betterment of farmers in the region. Their work is spread in the hilly as well as plain areas of Baghelkhand. In hilly areas, women farmers have been made the medium for promoting traditional farming. Self-help groups of women farmers have been created and they have established seed banks in the region. They also prepare bio-fertilisers and vermi-compost. This has led to conservation of indigenous seeds, made available seeds to farmers even during drought period and the other initiative to get their crops sold at good rates in markets have increased the earning of the farmers.

Paddy farming using indigenous seeds has been promoted in plains of Baghelkhand too. Sarjana organizes a ‘seed festival’ every year, which is attended by farmers in large numbers. Exhibition of indigenous seeds is put up and information on indigenous crops is exchanged.

Dahiyaand his organization have not only conserved and promoted indigenous seeds, but also put a focus on conservation of entire bio-diversity of the region including the herbs, medicinal and rare plants.

Seed Bank with the Support of MP State Biodiversity Board

Dahiya shares that he is linked with the MP State Biodiversity Board since the year 2005. B.M. Rathod was the secretary of the board then and he encouraged Dahiya for composition and compilation of folk literature including sayings, idioms and proverbs related to agriculture. Dahiya met numerous farmers and elders in villages for his compilation. This was published as a book named ‘Sayanan ke Thati’ by the Biodiversity Board.

Later, an indigenous seed bank was established in the Pithorabad village with the financial support of Biodiversity Board. The bank has as many as 200 indigenou svarieties of paddy seeds, 15 varieties of wheat and five varieties of gram. Also there are varieties of sanwa, jowar, kodo, kutki seeds apart from seeds of various vegetables.

The MP Biodiversity Board also promotes traditional knowledge based awareness apart from conservation of bio-diversity in the state.

Tour to Pithorabad on March 20-21

Pithorabad village is situated in the Unchehara block of Satna district. I had visited the village earlier too. I took a train from Piparia to Unchehara and proceeded to Pithorabad by bus. From the bus windows I could see the bare backs of local hills. There are almost no trees. Though it was the fall season and greenery was not expected, but there were even no trees. When I reached Pithorabad, it was already afternoon. It is a big village with a population of about 5000. Though it is like any other village in the region, but the association of Babulal Dahiya and his indigenous seeds and bio-diversity related work has made Pithorabad special.

200 Varieties of Indigenous Paddy and Diverse Farming

Babulal Dahiya says that he had 8 acres of agricultural land and he experiments with indigenous paddy varieties on 2 acre of this land. He also sows indigenous varieties on the other 6 acres and does not use any chemical fertilizer or pesticides. Now he has about 200 varieties of indigenous paddy seeds. Dahiya has studied the qualitative aspects of the indigenous paddy varieties. He sows them every year in his farm to study various aspects.

He showed me the paddy varieties. They were stuck neatly on pages of a register and it was an interesting view. The colourful seeds were attractive and diverse. Dahiya ji said that rice coming out of some of the varieties were white, while others were red. Some were black, some violet and some off-white. Some grains were broad, some fine, some roundish and some long grains. Some paddy crops were green, other were violet. Not only are the varieties diverse, but the tastes are also fantastic.

Some of the varieties are aromatic, some others are without aroma. Some crops are short-term, while others take time. Varieties like sarya, sikiya, shyamjir, dihula, sarekhani etc ripen within 70-75 days in light and shallow soil, while newari, jholar,kargi, sekungar etc ripen in 100-120 days. Varieties that are more long-term and ripen in 120-130 days include badal phool, kerakhamh, vishnubhog, dilbaksa and others.

Laila-majnu paddy produces two white rice grains, leaves of kalawati variety are black while ganjakali gives more produce. There is a reason to sow different variety and it depends on the soil type. If the soil type is light then short-term paddy is sown.

Some varieties are specifically sown for domestic use. Bajranga is such variety that is not digested fast. Some varieties are grown to be sold in market and profit could be earned. These varieties include ganjakali, nibari, kosamkhand and luchai. Some varieties are specially grown to be fed to guests – including kamalshri, tilsand, vishnubhog and badshah bhog.

In the areas infested by wild boars, varieties that have thorns on the crops are sown. There is a saying related to this – dhan bowey kargi; suwar khaye na samdhi. This related to a variety that has thorns in the flower cluster or the panicle and thus boars do not eat it and since the rice variety is red in colour, it is not fed to in-laws of children who are considered to be special guests.

Detailing the specialties of the indigenous paddy, Dahiya ji says that it is tasty and thus fetches good price in the market. Indigenous paddy ripens under influence of the weather. For example if the same variety of paddy is sown at different times, it ripens together. They do not get infested by pests and if infestation does happen, the pests could be controlled with bio-pesticides. They can be sustained by the use of cattle dung manure or vermi-compost. Farming the indigenous variety does not entail additional costs. Seeds saved at home, labour and care by the family members are enough to grow the crop.

Dahiya ji says that that the indigenous varieties have the capacity to adapt itself to the local climatic conditions. For example, while battling the long-drawn drought and growing in the local land for hundreds of years, the Baghelkhand indigenous variety has increased the length of its stem so that more water could be stored. In the later stage, it can sustain on the dew too. The imported/outside varieties do not have these capabilities.

14 Varieties of Indigenous Wheat

Dahiya ji took me to his farm, but the paddy had already been harvested. This time, he has experimented with traditional wheat. He has sown 14 varieties and is studying their qualitative aspects. He has collected the varieties from different districts of the state.

The varieties are called – kathia, kathui, sarwati, hansraj, gwala, bansi, khaira, mundi, pisi, paigambari, khapli, kala genhu, kala senkar and basia. Some of the varieties are of unknown name.

Also five varieties of gram were down. They are kala chana, chanouli, kabuli, karwariha and desi chana. The look of alsi (linseed) crop with red flowers was great. Dahiya ji said that some of the wheat varieties ripen without water or little water. With no use of chemical fertilizer or pesticide, the input cost of farming is almost zero. Only the cost of electricity due to drawing of water from tube-well is to be considered. The indigenous varieties are thus useful for the drought-hit areas.

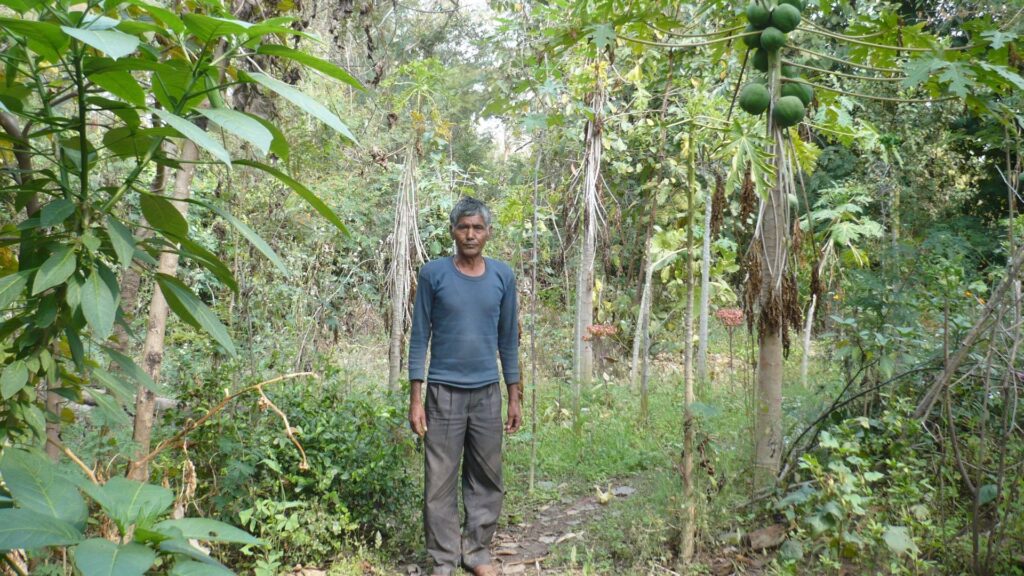

The Garden of Ramlotan Kushwaha

The next day, we visited the garden of Ramlotan Kushwaha, where he grows herbs, medicinal plants and various vegetables with the support of Sarjana Manch. He has also established a nursery, where he develops saplings sand sells them. Sometimes, even the forest department buys saplings from him. He listed the names of about 36 herbs/medicinal plants, fruit trees and vegetables that he grows off and on. He has several varieties of bottle gourd (louki) and lima beans (semi ki phalli). Some of the plants are of the varieties that have almost become extinct or are rare.

Tribal Women Farmers’ Group

Several women self-help groups have been formed in the villages of Parasmania Pahad. These groups are engaged in farming, mainly because most of the males in the village migrate for work. The responsibility of farming has fallen on women and they do much of farm work. Also, they diligently conserve the diversity and quality of seeds.

Seed banks have been established in two of the villages here – Dabra and Amdari. The banks lend seeds to farmers at the time of drought or other inclement weather. Together, the two banks cover farmers in about 30 villages. After crop is harvested, the farmers return 1.25 times of the seeds taken and a part of it is returned to the seed banks.

The women have also be trained in traditional farm related techniques like making of jivamrit, kalapani, vermi-compost and others. Most of the self-help groups are named after gods and goddesses like Saraswati Mahila Samuh, Jai Bada Dev Mahila Samuh, Kordarnath Mahila Samuh, Satain Mata samuh and others.

Sarjana organization had given seeds of traditional paddy varieties like luchai, dhanashree, saraiya, bohita to the women farmers to grow them in an acre of land per head. After keeping the meal requirements at homes, arrangement was done to get the produce sold at good price. The paddy was sent out to mega cities Delhi, West Bengal, Chennai and Bengaluru for sale. The average produce of paddy in the region is 10-12 quintal per acre. Dahiya says that the organization purchases the produce from the farmers at rates higher than the market rate and also arranges to sell it further. Last year the paddy was purchased at Rs 2500 per quintal.

Dahiya further says that due to the entire work, the traditional knowledge related to agriculture is returning amongst the women farmers. The seeds are kept safe in earthen safe rooms. The seeds of different varieties are kept in bottle gourd containers. Traditional methods of preservation and conservation of seeds are adopted. Women play a major role in selection of seeds, their conservation and preservation.

A Concluding Note

Overall, in this area of Satna district, diverse indigenous seeds are being conserved, preserved and promoted. Seeds are exchanged and along with them, traditional knowledge and information related to culture and heritage is also exchanged. The result is that even in the current times of climate change and inclement weather pattern, such indigenous seeds are being used for farming that can grow with less water, no water or even in drought conditions.

The use of indigenous variety for farming has led to food security among the farmers, something that was missing due to drought conditions and use of unsuitable crop varieties. The indigenous varieties are not only useful for nutrition, they also fetch good price in the market. Sarjana organization has proven that this is a sustainable initiative. It can be learnt from their efforts that seeds can be the basis for secure livelihood for small farmers. Bio-diversity and indigenous seeds based farming can provide employment, proper nutrition, good quality food and enhance income to the people. The need of the present times is to engage in farming that conserves soil and water and also provides sustainable livelihood. Babulal Dahiya and his organization have set up such a successful model.

The MP Biodiversity Board, set up under the Biodiversity Act of the government of India has played an important role in the entire initiative. The board not only provided a platform to Sarjana organization and Sahiya, but also helped in taking up an awareness campaign on indigenous seeds in entire Madhya Pradesh through them. Sarjana had undertaken a ‘beej bachao-kheti bachao’ (Save seeds, save agriculture) awareness rally in 2018 with help of Biodiversity Board. The rally covered 35 districts and encouraged farmers to take farming based on indigenous seeds. This shows that government support can play a very important role in such initiatives and their success.

Sarjana and Dahiya ji have done the all important work of conserving and preserving the indigenous seeds that were on the verge of extinction. Their initiative also led to empowerment of women farmers at a time when most males had migrated for work and there was crisis of livelihood and employment. Since the indigenous seeds-based farming is mostly dependent on manual labour, women do it easily.

The need to promote indigenous seeds had become critical because Baghelkhand had witnessed severe drought, economic crisis and inclement weather cycles. In such situation, the seed banks set up by Sarjana came as a big relief as the farmers would not have had seeds for farming otherwise. It is to be hoped that the indigenous seeds-based farming, which requires almost no additional economic input will prove to be a good model to save farmers from economic crisis.